The Narrative Question

I’m particularly amused by McLaren’s quote about not taking the Bible literally but then he proceeds to take the Bible… literally. Here’s an example:

It is patently obvious to me that these stories aren’t intended to be taken literally, although it didn’t used to be so obvious, and I know it won’t be so now for some of my readers. It is also powerfully clear to me that these nonliteral stories are still to be taken seriously and mined for their rich meaning, because they distill time-tested, multilayered wisdom—through deep mythic language—about how our world came to be what it has become. They’re intended, as all sacred creation narratives are, to situate and orient us in a story, so we will know how to live. (p. 48)

Then:

Scene 1. God tells Adam and Eve they are free (this is a primary condition of their existence, 2:16) with one exception. If they eat of one specific tree, on the day they eat, they will die. Notice, the text does not say they will be condemned to hell, be “spiritually separated from God,” be pronounced “fallen” or “condemned,” or be tainted with something called “original sin” that will be passed on to their children. There is only one consequence indicated by the text: they will die—not spiritually die, not relationally die, not ontologically die, but simply die. And not die eventually, but on the day they eat. (p. 49)

McLaren argues that there is no literal fall—a term he argues we’ve been “brainwashed” into believing through our reading of the Bible from a Greco-Roman perspective. In fact, he asserts Genesis recounts a story initially of ascents:

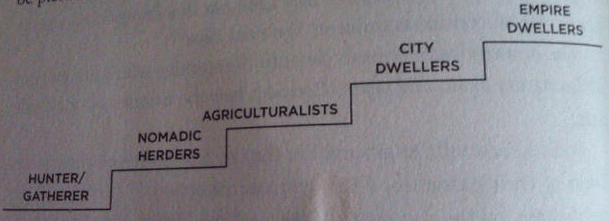

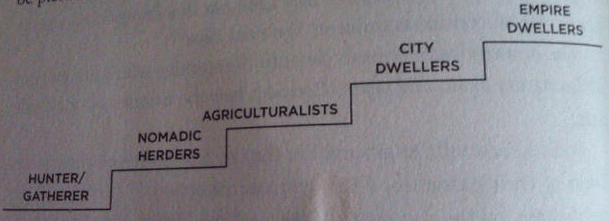

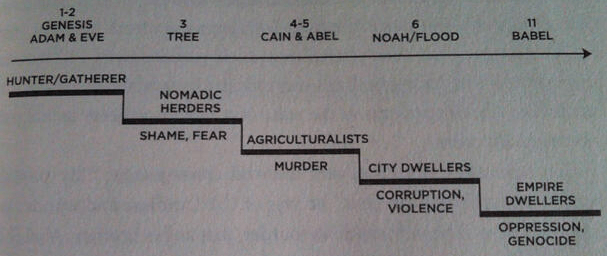

It is a first stage of ascent as human beings progress from the life of hunter-gatherers to the life of agriculturalists and beyond. Their journey could be pictured like this:

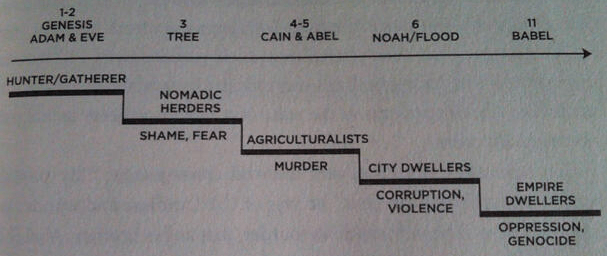

But also of a descent:

But the ascent is ironic, because with each gain, humans also descend into loss. They descent (or fall—there’s nothing wrong with the word itself, just the unrecognized baggage that may come with it) from the primal innocence of being naked without shame in one another’s presence.

Each step of socioeconomic and technological ascent thus makes possible new depths of moral evil and social injustice. (p. 50-51)

As humans, with progress (implication of ascent) there is also loss (which in turn puts humans on a descent). Thereby, we now lose the vertical pattern of Platonic perfection-ideal as expressed through the Greco-Roman view of Eden but have a more progressive view of the Bible—a stepping stone, if you will.

If Genesis sets the stage for the biblical narrative, this much is unmistakably clear: God’s unfolding drama is not a narrative shaped by the six lines in the Greco-Roman scheme of perfection, fall, condemnation, salvation, and heavenly perfection or eternal perdition. It has a different story line entirely. It’s a story about the downside of “progress”—a story of human foolishness and God’s faithfulness, the human turn toward rebellion and God’s turn toward reconciliation, the human intention toward evil and God’s intention to overcome evil with good. It begins with God creating a good world, continues with human beings creating evil, and concludes with God creating good outcomes that overcome human evil. We might say it is the story of goodness being created and re-created: God creates a good world, which humans damage and savage, but though humans have evil intent, God still creates good, and God’s good prevails. Good has the first word, and good has the last. (p. 54)

If this view sets the stage for how to read the Bible, we are certainly in for a very interesting (and bumpy) ride.

In Chapter 6, McLaren argues that the beginning of his quest to view Christianity through a new lens was shaped by his liberal arts education and bolstered by a lack of formal theology training. I found this quote interesting:

Deconstruction is not destruction, as many erroneously assume, but rather careful and loving attention to the construction of ideas, beliefs, systems, values, and cultures.

Merriam-Webster defines deconstruction this way:

1 : a philosophical or critical method which asserts that meanings, metaphysical constructs, and hierarchical oppositions (as between key terms in a philosophical or literary work) are always rendered unstable by their dependence on ultimately arbitrary signifiers

2 : the analytic examination of something (as a theory) often in order to reveal its inadequacy

Deconstruction is not careful and loving attention to construction, no matter what McLaren says. Deconstruction is critical assessment performed in order to reveal inadequacies.

But McLaren is openly stating that he’s reading the Bible through a literary lens where he can identify protagonists, antagonists, plot, tension, conflict, resolution, and character development.

So as we head into Exodus, we read of a God who “sides with the oppressed, and God confronts oppressors with intensifying negative consequences until they change their ways, and in the end the oppressors are humbled and the oppressed are liberated.”

I can’t help but comment that McLaren is back to nonliteralism now as he says God sends a “firm but gentle” plague on the Nile River that “turns red like blood.” But let’s read what Exodus 7:14-21 says. In fact, let’s use The Message version, Eugene Peterson’s paraphrase of what the Bible says:

God said to Moses: “Pharaoh is a stubborn man. He refuses to release the people. First thing in the morning, go and meet Pharaoh as he goes down to the river. At the shore of the Nile take the staff that turned into a snake and say to him, ‘God, the God of the Hebrews, sent me to you with this message, “Release my people so that they can worship me in the wilderness.” So far you haven’t listened. This is how you’ll know that I am God. I am going to take this staff that I’m holding and strike this Nile River water: The water will turn to blood; the fish in the Nile will die; the Nile will stink; and the Egyptians won’t be able to drink the Nile water.'”

God said to Moses, “Tell Aaron, ‘Take your staff and wave it over the waters of Egypt—over its rivers, its canals, its ponds, all its bodies of water—so that they turn to blood.’ There’ll be blood everywhere in Egypt—even in the pots and pans.”

Moses and Aaron did exactly as God commanded them. Aaron raised his staff and hit the water in the Nile with Pharaoh and his servants watching. All the water in the Nile turned into blood. The fish in the Nile died; the Nile stank; and the Egyptians couldn’t drink the Nile water. The blood was everywhere in Egypt.

The quote above is simply a paraphrase—someone’s interpretation of what is occurring in the Bible. I’m amazed that McLaren is so intent on reading the Bible non-literally that he tries to explain away what’s happening in the Bible through literal means: “Ironically, perhaps through a red tide, the Nile turns red like blood.” As a result of McLaren’s literary reading of Biblical passages, he begins to make literal assumptions about these passages that aren’t there.

On page 58, McLaren says “God never works directly, only indirectly” and reduces the plagues often seen as something extraordinary and supernatural into nothing more than ordinary and natural. He diminishes the work of God.

McLaren argues the Bible presents three narratives:

- God as creator

- God as liberator from external and internal oppression

- God as reconciler

After reading beautiful literary passages from Hosea, Joel, and Isaiah, McLaren encourages his readers to see the future as something that “is not fatalistically predetermined” but rather see history as “live”—“unscripted, unrehearsed reality, happening now—really happening.” (p. 62-63) Here, McLaren rejects the premise of a predetermined, foreknown future by God (Jeremiah 29:11; Acts 2:22-23; Romans 8:28-30; I Corinthians 2:7; Ephesians 1:5,11).

Then McLaren attempts to literalize Scripture within a modern framework despite saying, “As this approach relieves of literalistic interpretations, it frees us to let the poetry work as poetry is supposed to”:

Swords into plowshares. Today that would mean dreaming about tanks being melted down into playground jungle gyms and machine guns being recast as swing sets. (p. 63)

That’s just one example. It’s a clever reading of the passage but the fact of the matter is, McLaren is trying to take the literal, make it literary, and then convert the literary as the literal he wants to see. To put it bluntly, McLaren is reading things in the Bible that simply aren’t there.

McLaren is very good at igniting passion and hope for a better tomorrow that seems as if it can occur today.

If the Genesis story sets the stage by giving us a sacred vision of the past, and if the Exodus story situates us in the sacred present on a pilgrimage toward external and internal liberation, then the story of the peace-making kingdom ignites our faith with a sacred vision of the future, a vision of hope, a vision of love. It represents a new creation, and a new exodus—a new promised land that isn’t one patch of ground held by one elite group, but that encompasses the whole earth. It acknowledges that whatever we have become or ruined, there is hope for a better tomorrow; whatever we have achieved or destroyed, new possibilities await us; no matter how far we have come or backslidden, there are new and more glorious adventures ahead. And, the prophets aver, this is not just a human pipe dream, wishful thinking, whistling in the dark; this hope is the very word of the lord, the firm promise of the living God.

Perhaps I’m not as optimistic or those darn Greco-Roman glasses keep getting in the way.

Again, I appreciate McLaren’s attempt to read the Bible with a new perspective but there needs to be a balance between the literal and literary interpretations. I understand that some people Bible see the Bible as purely a literal work of God; others see the Bible as nothing more than a beautiful piece of literature. McLaren looks as the Bible as a beautiful piece of literature and then tries to recast it into a literal work with explanations that are a stretch. Frankly, McLaren’s attempt at a new kind of Christianity appears headed extremely off-course as I go into reading Chapter 7.

The Emergent Church has also served as a rubber band for those who have escaped from the sharp talons of legalistic Christianity. The movement has enabled many Christians to retain certain core truths but make their faith flexible and pliable—when exercised, this faith can be tested and stretched without breaking and completely falling apart. Bell, in Velvet Elvis, refers to legalistic faith as a brick wall: pull one brick out and the rest of the wall crumbles because its support hinges on that one brick.

The Emergent Church has also served as a rubber band for those who have escaped from the sharp talons of legalistic Christianity. The movement has enabled many Christians to retain certain core truths but make their faith flexible and pliable—when exercised, this faith can be tested and stretched without breaking and completely falling apart. Bell, in Velvet Elvis, refers to legalistic faith as a brick wall: pull one brick out and the rest of the wall crumbles because its support hinges on that one brick.