This is a repost on my thoughts on celebrating Black History Month from last year. I believe that once the American school system fully integrates—not only Black culture but also all other racial and ethnic groups into American history and American literature curriculums—will America be able to move forward in transcending racial barriers. As it stands, the election of a biracial president is simply not enough (even though many people thought and hoped it would be).

February 28th marks the end of Black History Month for 2010—something I chose not to take part in this year. Not because I have any personal objections to commemorating Black American history or anything; I was simply preoccupied with other things like reading up and writing about the Emergent Church. I also read the hardcover version of Joseph C. Phillips’s book, He Talk Like A White Boy, and had hoped to provide a review sometime during February but upon receiving the paperback version, I discovered more essays were added so a book review on that has been put on hold for now.

For some time, I have been mulling on and off about the issue of Black pride. A counter in this discussion is often, “Why is it okay for people to have Black pride and if a White person has White pride, it’s White supremacy and racism?” While I can see that as a valid argument, I submit the idea that Black in America has evolved from a purely racial context to a mostly cultural context.

Many white people (or Caucasians) in America likely know their ethnic background based on their last name or some kind of genealogy. No one knocks Italian-Americans for having Italian pride or Irish-Americans for celebrating their heritage on good ol’ St. Patty’s Day. Americans who have an Italian or Irish background are, quite frankly, part of the White race but choose to emphasize their ethnicity rather than simply the color of their skin. Even those who are of white supremacy organizations are known as WASPs (White Anglo-Saxon Protestants). This WASP indication places them in the context of British, Germanic, and possibly even Danish ethnicity. I daresay most people don’t have a problem with Americans celebrating their Polish or Germanic heritage.

But when it comes to Black people, they are slammed for choosing to identify themselves as African-American: “Oh, you’re not really African-American. Look at Kwame over there. His parents are from Zimbabwe—he’s a real African-American.” So what are Black people in America?

Well, simply put, Black people in America are Black Americans. Should they choose to identify themselves as African-American, that is purely their prerogative even if the last ancestor that hailed from Africa was back in 1776. The fact of the matter is that most people who are considered Black in the United States are most likely of Sub-Saharan African descent.

But 1776 is a long way away from 2010. A Black American stepping onto African soil would feel strangely at home and strangely out of place at the same time. Joseph C. Phillips writes:

There is a romanticism associated with Africa that runs deep in the black community. … For me, the bloom fell off the African rose fairly early. Maybe it was when a soldier armed with an AK-47 boarded our bus on the way to the hotel. Or maybe it was when I realized Nigeria was so rife with corruption that cashing a traveler’s check was a major ordeal. The romance was certainly gone once we drove through the countryside and witnessed poverty like I have never seen before. … Alas, my visit to Africa proved less of a homecoming than an affirmation of my Americanness.

… Later in the trip, I had an opportunity to meet socially with several Nigerians. Among my fellow travelers there was a tendency to speak of American blacks as if we were Africans living abroad, everyday Africans did not share this view. They saw us as Americans, first and always. Even to the Nigerians I met who, by and large, were educated in the West we were as American as, well, George Bush.

… That’s not to say I did not feel the tug of Africa at all. I discovered that it is very difficult to be a black American and experience Africa purely as an American. Everywhere I looked, there were bits and pieces of myself.

Black Americans, like Italian-Americans, Irish-Americans, or Polish-Americans, are very much African but moreso very much American.

The estimated date for final importation of slaves from Africa is in the mid-1800s. That leaves a century and a half in which generational Black Americans are most likely to have had ancestors directly from Africa. Within two centuries, however, Black Americans have evolved from African culture and developed their own kind of culture relative to the United States alone. As a result, being Black in America is not simply a matter of race, it is also a matter of culture. Race and culture are now inevitably intertwined.

So when I think of Black pride, I don’t necessarily think of Black Americans taking pride in the color of their skin but rather who they are as a culture that happens to be connected to the color of their skin. I do like the way the writer of the wikipedia entry on African American culture put it:

For many years African American culture developed separately from mainstream American culture because of the persistence of racial discrimination in America, as well as African American slave descendants’ desire to maintain their own traditions. Today, African American culture has become a significant part of American culture and yet, at the same time, remains a distinct cultural body.

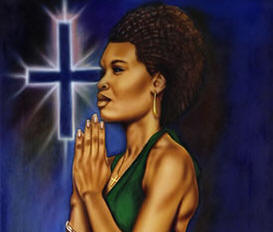

There is a style of worship, a style of music, a form of art, and a form of dance that is intrinsic to Black American culture. While some of it may be derived from Africa, it has evolved over the centuries to become uniquely Black American (or African-American, if you will).

There is a style of worship, a style of music, a form of art, and a form of dance that is intrinsic to Black American culture. While some of it may be derived from Africa, it has evolved over the centuries to become uniquely Black American (or African-American, if you will).

But then I wonder whether if it’s sinful to have Black pride within a cultural context and I don’t believe so. Just like the ethnic pride of being Spanish, Germanic, or Swedish, I don’t believe pride in immutable, nonsinful qualities is wrong—it’s the way God made us! Where it does start to go wrong is when these groups use their ethnic position as a form of superiority, especially in order to oppress one group over another. Black supremacy is just as wrong as white supremacy, no matter what the context.

So when I think of Black History Month, and heading into March Women’s History (or Herstory, whatever you want to call it) Month, I don’t see such remembrances as an issue of superiority of one group over another (black vs. white or male vs. female). Rather, I see them as a way of celebrating and reflecting on the accomplishments of formerly oppressed groups that overcame significant obstacles to become thriving members of American society.

I watched hoping to see a well-done opening act only to find Jamie Foxx, butchering the Moonwalk and doing a poor imitation of Michael Jackson’s dance moves. I smiled, assuming Foxx was being comedic and doing the best he could. When Foxx was done, he went on a mini-rant about how Michael Jackson was a “black man” and “he belonged to us.” My husband immediately flipped the channel and said, “I am not watching anymore of this racist garbage.” He subsequently went on to ban BET from our home.

I watched hoping to see a well-done opening act only to find Jamie Foxx, butchering the Moonwalk and doing a poor imitation of Michael Jackson’s dance moves. I smiled, assuming Foxx was being comedic and doing the best he could. When Foxx was done, he went on a mini-rant about how Michael Jackson was a “black man” and “he belonged to us.” My husband immediately flipped the channel and said, “I am not watching anymore of this racist garbage.” He subsequently went on to ban BET from our home. Those two questions run through my mind at least once a day. (I’m probably providing a conservative estimate on that front.) Well, here are the basic answers to each question:

Those two questions run through my mind at least once a day. (I’m probably providing a conservative estimate on that front.) Well, here are the basic answers to each question: