“It wasn’t a phenomenon in the Black community, I don’t think. … It is a middle-class/upper-middle-class, White departure from orthodoxy.” — John Piper

H/T: Michael Krahn

Attempting to live and breathe for an audience of one

“It wasn’t a phenomenon in the Black community, I don’t think. … It is a middle-class/upper-middle-class, White departure from orthodoxy.” — John Piper

H/T: Michael Krahn

I was looking into attending a Christian conference for bloggers and maybe meeting with other Christian blogger-types in the hopes of making real-life connections. When I stumbled upon the conference site, I got the sense that the conference was geared toward married women with children although it was not something that was explicitly stated. After a bit of researching, I very much indeed realized that every woman at that conference had a husband and at least one child and most had dubbed themselves “mommy bloggers.”

Then I thought about the Christian women who aren’t mommy bloggers and how left out they must feel. It’d be kind of rude to have a Christian conference for wives who are childless bloggers or a Christian conference solely for single women. The thought of such an exclusionary meeting is even kind of depressing.

I know several single Christian women and I can only imagine the pain they must endure as ignorant women (like me) babble on about how great their husbands are or how wonderful and sweet their children can be. I also wonder if these same women who desire children get particularly annoyed at parents who complain frequently about their children.

But I digress.

God has called us to live in community and not divisiveness which makes me wonder if there is a place for all Christian women to come together—a conference where women in all walks of life can share their faith and fellowship with one another. I understand it’s harder for single Christian women to take time off for a conference but that doesn’t mean the option to do so should be closed off to them. And a childless wife shouldn’t feel shut out of conferences simply because she is not a mother (for whatever reason).

Gary Thomas, author of the book Devotions for a Sacred Marriage (derived from the wildly successful book Sacred Marriage), had a chapter titled, “Thoughtlessly Cruel” about performing actions that weren’t intended to be hurtful but were anyway. It made me wonder if, in our quest to find people who are just like us and in our stage of life, we are thoughtlessly cruel by shutting them out. Many of us don’t intend to be rude, divisive, or cliquish… it just naturally happens that way. So we end up with groups like “mommy bloggers” then… everybody else. (I’m a semi-regular blogger without a blogger title.)

Please don’t get me wrong: I am not knocking mommy bloggers (although I’ll admit to not being fond of the term). Mommy bloggers have become such a powerful force within recent years that advertisers and merchants are taking advantage of this group by hosting giveways on their blogs. Mommy bloggers are quite the influential group and I have a few mommy blogger friends myself.

But what about the childless bloggers? The unmarried bloggers (who may or may not be childless)? Perhaps there’s a group I’m even forgetting. Don’t these people matter?

Beyond Christian conferences, however, my challenge is really directed to believers who are part of a local church. How often do we overlook the people who are single but have a strong desire for marriage and children? How often do we ignore the pain of couples who desire a child so greatly but have not been able to conceive or adopt? And how have we shut out couples who have prayerfully chosen to remain childless in a religious culture that makes it an imperative to have children?

Just something to consider.

*

(Side note: In the future, I hope to be a blogger who happens to be a mom rather than a mommy blogger. I worry that the identity of becoming a mother will take me over and swallow me whole leaving me with nothing but just a shell of who I used to be. But that is a post for another day.)

My most recent post on changes wasn’t about my friend and her baby so much as it was about using a recent example to highlight my difficulty with change. Namely change in stages of life. I’m a writer but sometimes I don’t write things so well.

To continue with the thought though—at the risk of totally botching this up, I wonder how I’d handle the transition to having a child of my own. I’m not pregnant or anything but I think about having a tiny, little life of my own and I wonder how much more would I be near the epicenter of my own earthquake. I like the idea of kids but am not sure that I’d do so well with them in reality. And then that puts me in a stage of life far beyond my New York friends and if I’m honest, that’s the last thing I want to do because then I wonder if that would be the final break, the final straw in us not being able to relate to one another at all.

I read a quote somewhere, might have even been T. D. Jakes in Essence magazine but he said that some people come into your life for a season and when that season ends, God takes them away. It’s not that they’re bad or you’re bad, it’s just that the season is over and it’s time to part ways.

Thinking about that always made me sad because I lament the loss of friendships all the time.

I feel sad that I never kept in touch with Tara, my best friend in kindergarten. I feel sad that a girl I once considered my best friend in elementary school decided to betray me by kissing the boy I’d hopelessly become infatuated with and prank calling me to tell me I was a lesbian. (*69 was a Godsend at the time.) I also feel sad that i lost touch with a girl who was an amazing friend and no-nonsense in my freshman year of high school. And how many more friendships have I lost or missed out on through my college years? Too numerous to count.

I suppose I’m focusing on the relational aspect of change. But I don’t do so well with moving away from places outside of New York although I’m doing all right just outside Philly in Pennsylvania. Since I’m typing this on my iTouch, I’ll leave the subject as it stands now and maybe elaborate on this post with different aspects of my life in which I have trouble adapting to change.

Leaving New York was really a BIG one. But NY became an idol so there’s more to the story.

From Donald Miller’s Blue Like Jazz:

Penny has painful memories of her mother slipping into delusion, first believing John Kennedy was her lover, then claiming she was being hunted by the FBI. Her mother was diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic when Penny was a child. Today Penny’s mother lives on the streets of Seattle where she adamantly refuses help from anyone, including Penny.

Penny once told me that no matter how gingerly she put the puzzle of her past together, she was always cut by the sharp edges: the fact that her mother was stoned while giving birth, the enticing but deceptive delusions presented to her as a child, and the breakup, not only of her mother from her father, but her mother from all reality. When I talk to Penny about driving up to Seattle to meet her mother, she tells me that I wouldn’t enjoy the experience, that her mother will hate me.

“She hates everybody, Don. She thinks people are out to get her. If I call her on the phone in the shelter, she will come to the phone and hang it up. She doesn’t answer my letters. She probably doesn’t even open them.”

“But she was normal at one time, right?” I once asked.

“Yes, she was beautiful and fun. I loved my mom, Don, and I still do. But I hate that her mind has been taken. I hate that I can’t have normal interaction with her.”

Penny is not alone in her sentiments; I felt the same way about my father before he died.

I don’t deal with change so well. I don’t deal with hope so well either so we’ll leave any discussions of Obama’s marketing slogan for the 2008 presidential election for another day.

Change is hard for me. My husband’s most frequent comment to me is that I live in the past. He’s right; I’ll readily acknowledge that I do. Especially for someone who insists on planning for the future.

When it comes to friendships, change is especially hard for me. The changes that occurred in my friendship after I made the transition from being a single woman to a married woman were difficult. My friends were no longer first in my life; my husband now was—and that’s how it had to be from that point on.

This grieved me incredibly. I’m sure it grieved them more. Not only did I get married but I left New York state soon after to move hundreds of miles away to Kentucky. They probably felt as though I’d left them behind. And I must acknowledge that I did.

Now, I have a close friend who has just given birth to a beautiful baby girl. I am happy for her. But as I visited her and her husband today, their main attentions centered around this tiny, helpless life who needed care and attentiveness. It was then that I experienced what my single friends must have felt when I got married: I felt left behind.

My friend and her husband have moved into a new stage of life that includes a child. And today, I felt the sudden shift in our friendship like Californians feel the shift of the earth underneath. We initially became friends at church because we were one of the few young married couples who were still childless. Not that it was a stage of life my friend particularly wanted or liked but it was where she was and it was where I was and it was one of the reasons we were able to become good friends.

I have lots of friends who have children but I suppose I’ve always had a hard time relating to them because they’re moms and I’m not and I hate bugging them because their children are their first priorities. And I’ve never seen this particular friend that way but with her new daughter, that’s where our friendship is headed. And I’m sad and I grieve a bit because even though we’ll still be friends, our friendship will never be the same.

My heart now sincerely goes out to my single friends who lost me to a husband. I understand how they feel now.

From Donald Miller’s Blue Like Jazz:

A long time ago I went to a concert with my friend Rebecca. … I heard this folksinger was coming to town, and I thought she might like to see him because she was a singer too. … Between songs, though, he told a story that helped me resolve some things about God. The story was about his friend who is a Navy SEAL. He told it like it was true, so I guess it was true, although it could have been a lie.

The folksinger said his friend was performing a covert operation, freeing hostages from a building in some dark part of the world. His friend’s team flew in by helicopter, made their way to the compound and stormed into the room where the hostages had been imprisoned for months. The room, the folksinger said, was filthy and dark. The hostages were curled up in a corner, terrified. When the SEALs entered the room, they heard the gasps of the hostages. They stood at the door and called to the prisoners, telling them they were Americans. The SEALs asked the hostages to follow them, but the hostages wouldn’t. They sat there on the floor and hid their eyes in fear. They were not of healthy mind and didn’t believe their rescuers were really Americans.

The SEALs stood there, not knowing what to do. They couldn’t possibly carry everybody out. One of the SEALs, the folksinger’s friend, got an idea. He put down his weapon, took off his helmet, and curled up tightly next to the other hostages, getting so close his body was touching some of theirs. He softened the look on his face and put his arms around them. He was trying to show them he was one of them. None of the prison guards would have done this. He stayed there for a little while until some of the hostages started to look at him, finally meeting his eyes. The Navy SEAL whispered that they were American and were there to rescue them. Will you follow us? he said. The hero stood to his feet and one of the hostages did the same, then another, until all of them were willing to go. The story ends with all the hostages safe on an American aircraft carrier.

I never liked it when the preachers said we had to follow Jesus. Sometimes they would make Him sound angry. But I liked the story the folksinger told. I liked the idea of Jesus becoming man, so that we would be able to trust Him, and I like that He healed people and loved them and cared deeply about how people were feeling.

When I understood that the decision to follow Jesus was very much like the decision the hostages had to make to follow their rescuer, I knew then that I needed to decide whether or not I would follow Him. The decision was simple once I asked myself,

- Is Jesus the Son of God,

- are we being held captive in a world run by Satan, a world filled with brokenness, and

- do I believe Jesus can rescue me from this condition?

I like that story about the Navy SEAL, true or not. I like to think of Jesus as my rescuer becoming like me, crouching beside me in my brokenness, putting his arm around my shoulder, and asking me to follow Him.

I like that very much. Thank you for that illustration, Mr. Miller.

I’m particularly amused by McLaren’s quote about not taking the Bible literally but then he proceeds to take the Bible… literally. Here’s an example:

It is patently obvious to me that these stories aren’t intended to be taken literally, although it didn’t used to be so obvious, and I know it won’t be so now for some of my readers. It is also powerfully clear to me that these nonliteral stories are still to be taken seriously and mined for their rich meaning, because they distill time-tested, multilayered wisdom—through deep mythic language—about how our world came to be what it has become. They’re intended, as all sacred creation narratives are, to situate and orient us in a story, so we will know how to live. (p. 48)

Then:

Scene 1. God tells Adam and Eve they are free (this is a primary condition of their existence, 2:16) with one exception. If they eat of one specific tree, on the day they eat, they will die. Notice, the text does not say they will be condemned to hell, be “spiritually separated from God,” be pronounced “fallen” or “condemned,” or be tainted with something called “original sin” that will be passed on to their children. There is only one consequence indicated by the text: they will die—not spiritually die, not relationally die, not ontologically die, but simply die. And not die eventually, but on the day they eat. (p. 49)

McLaren argues that there is no literal fall—a term he argues we’ve been “brainwashed” into believing through our reading of the Bible from a Greco-Roman perspective. In fact, he asserts Genesis recounts a story initially of ascents:

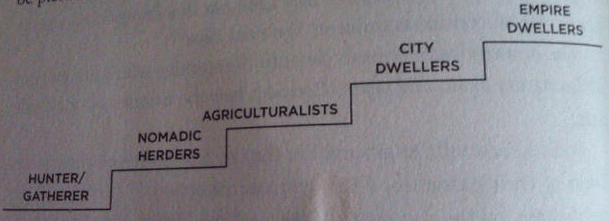

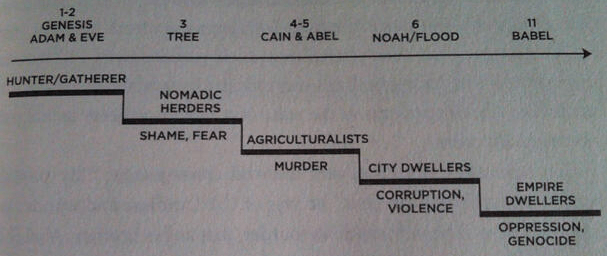

It is a first stage of ascent as human beings progress from the life of hunter-gatherers to the life of agriculturalists and beyond. Their journey could be pictured like this:

But also of a descent:

But the ascent is ironic, because with each gain, humans also descend into loss. They descent (or fall—there’s nothing wrong with the word itself, just the unrecognized baggage that may come with it) from the primal innocence of being naked without shame in one another’s presence.

Each step of socioeconomic and technological ascent thus makes possible new depths of moral evil and social injustice. (p. 50-51)

As humans, with progress (implication of ascent) there is also loss (which in turn puts humans on a descent). Thereby, we now lose the vertical pattern of Platonic perfection-ideal as expressed through the Greco-Roman view of Eden but have a more progressive view of the Bible—a stepping stone, if you will.

If Genesis sets the stage for the biblical narrative, this much is unmistakably clear: God’s unfolding drama is not a narrative shaped by the six lines in the Greco-Roman scheme of perfection, fall, condemnation, salvation, and heavenly perfection or eternal perdition. It has a different story line entirely. It’s a story about the downside of “progress”—a story of human foolishness and God’s faithfulness, the human turn toward rebellion and God’s turn toward reconciliation, the human intention toward evil and God’s intention to overcome evil with good. It begins with God creating a good world, continues with human beings creating evil, and concludes with God creating good outcomes that overcome human evil. We might say it is the story of goodness being created and re-created: God creates a good world, which humans damage and savage, but though humans have evil intent, God still creates good, and God’s good prevails. Good has the first word, and good has the last. (p. 54)

If this view sets the stage for how to read the Bible, we are certainly in for a very interesting (and bumpy) ride.

In Chapter 6, McLaren argues that the beginning of his quest to view Christianity through a new lens was shaped by his liberal arts education and bolstered by a lack of formal theology training. I found this quote interesting:

Deconstruction is not destruction, as many erroneously assume, but rather careful and loving attention to the construction of ideas, beliefs, systems, values, and cultures.

Merriam-Webster defines deconstruction this way:

1 : a philosophical or critical method which asserts that meanings, metaphysical constructs, and hierarchical oppositions (as between key terms in a philosophical or literary work) are always rendered unstable by their dependence on ultimately arbitrary signifiers

2 : the analytic examination of something (as a theory) often in order to reveal its inadequacy

Deconstruction is not careful and loving attention to construction, no matter what McLaren says. Deconstruction is critical assessment performed in order to reveal inadequacies.

But McLaren is openly stating that he’s reading the Bible through a literary lens where he can identify protagonists, antagonists, plot, tension, conflict, resolution, and character development.

So as we head into Exodus, we read of a God who “sides with the oppressed, and God confronts oppressors with intensifying negative consequences until they change their ways, and in the end the oppressors are humbled and the oppressed are liberated.”

I can’t help but comment that McLaren is back to nonliteralism now as he says God sends a “firm but gentle” plague on the Nile River that “turns red like blood.” But let’s read what Exodus 7:14-21 says. In fact, let’s use The Message version, Eugene Peterson’s paraphrase of what the Bible says:

God said to Moses: “Pharaoh is a stubborn man. He refuses to release the people. First thing in the morning, go and meet Pharaoh as he goes down to the river. At the shore of the Nile take the staff that turned into a snake and say to him, ‘God, the God of the Hebrews, sent me to you with this message, “Release my people so that they can worship me in the wilderness.” So far you haven’t listened. This is how you’ll know that I am God. I am going to take this staff that I’m holding and strike this Nile River water: The water will turn to blood; the fish in the Nile will die; the Nile will stink; and the Egyptians won’t be able to drink the Nile water.'”

God said to Moses, “Tell Aaron, ‘Take your staff and wave it over the waters of Egypt—over its rivers, its canals, its ponds, all its bodies of water—so that they turn to blood.’ There’ll be blood everywhere in Egypt—even in the pots and pans.”

Moses and Aaron did exactly as God commanded them. Aaron raised his staff and hit the water in the Nile with Pharaoh and his servants watching. All the water in the Nile turned into blood. The fish in the Nile died; the Nile stank; and the Egyptians couldn’t drink the Nile water. The blood was everywhere in Egypt.

The quote above is simply a paraphrase—someone’s interpretation of what is occurring in the Bible. I’m amazed that McLaren is so intent on reading the Bible non-literally that he tries to explain away what’s happening in the Bible through literal means: “Ironically, perhaps through a red tide, the Nile turns red like blood.” As a result of McLaren’s literary reading of Biblical passages, he begins to make literal assumptions about these passages that aren’t there.

On page 58, McLaren says “God never works directly, only indirectly” and reduces the plagues often seen as something extraordinary and supernatural into nothing more than ordinary and natural. He diminishes the work of God.

McLaren argues the Bible presents three narratives:

After reading beautiful literary passages from Hosea, Joel, and Isaiah, McLaren encourages his readers to see the future as something that “is not fatalistically predetermined” but rather see history as “live”—“unscripted, unrehearsed reality, happening now—really happening.” (p. 62-63) Here, McLaren rejects the premise of a predetermined, foreknown future by God (Jeremiah 29:11; Acts 2:22-23; Romans 8:28-30; I Corinthians 2:7; Ephesians 1:5,11).

Then McLaren attempts to literalize Scripture within a modern framework despite saying, “As this approach relieves of literalistic interpretations, it frees us to let the poetry work as poetry is supposed to”:

Swords into plowshares. Today that would mean dreaming about tanks being melted down into playground jungle gyms and machine guns being recast as swing sets. (p. 63)

That’s just one example. It’s a clever reading of the passage but the fact of the matter is, McLaren is trying to take the literal, make it literary, and then convert the literary as the literal he wants to see. To put it bluntly, McLaren is reading things in the Bible that simply aren’t there.

McLaren is very good at igniting passion and hope for a better tomorrow that seems as if it can occur today.

If the Genesis story sets the stage by giving us a sacred vision of the past, and if the Exodus story situates us in the sacred present on a pilgrimage toward external and internal liberation, then the story of the peace-making kingdom ignites our faith with a sacred vision of the future, a vision of hope, a vision of love. It represents a new creation, and a new exodus—a new promised land that isn’t one patch of ground held by one elite group, but that encompasses the whole earth. It acknowledges that whatever we have become or ruined, there is hope for a better tomorrow; whatever we have achieved or destroyed, new possibilities await us; no matter how far we have come or backslidden, there are new and more glorious adventures ahead. And, the prophets aver, this is not just a human pipe dream, wishful thinking, whistling in the dark; this hope is the very word of the lord, the firm promise of the living God.

Perhaps I’m not as optimistic or those darn Greco-Roman glasses keep getting in the way.

Again, I appreciate McLaren’s attempt to read the Bible with a new perspective but there needs to be a balance between the literal and literary interpretations. I understand that some people Bible see the Bible as purely a literal work of God; others see the Bible as nothing more than a beautiful piece of literature. McLaren looks as the Bible as a beautiful piece of literature and then tries to recast it into a literal work with explanations that are a stretch. Frankly, McLaren’s attempt at a new kind of Christianity appears headed extremely off-course as I go into reading Chapter 7.

As Rebecca St. James sung about Jesus through my headphones, I spent my entire walk on a nice, sunny day lamenting about how I didn’t have someone to share it with.

How foolish.

“What is the overarching story line of the Bible?” McLaren asks. His response, which really comes across as more of an authoritative answer in some areas, is that current Christianity reads the Bible through the lens of an Aristotelian-Platonic universe. He calls it a Greco-Roman story line where Christians see God as something akin to Zeus or Jupiter—a perfect heavenly being that is ready to strike down flawed creatures on a whim—and if certain creatures never reach the Platonic ideal of heaven then they are sent down to a Greek Hades, a hell, “imagery misappropriated from Jesus’ parables and sermons.” (p. 44)

McLaren may have a point. Perhaps Christians read the Bible through the lens of this Greco-Roman narrative, but it’s worth pointing out that Jesus’ story developed within a Roman context. (Pilate? Caesar, anyone?) And that the New Testament was written in Greek. As a result, I disagree with McLaren that this Greco-Roman narrative is necessarily bad. Instead, I argue that the Greco-Roman narrative provides a form of context as a result of being influenced by the Roman Empire and the original language of the New Testament. This influence is inescapable.

McLaren also makes the point that we should read the Bible for the Judaic narrative that it is—as Jesus would have read it. That is a fair and valid point as well. Therein lies the challenge: reading the Bible for what it is without inserting a post-Jesus historical lens (ie, reading the Bible through a post-Reformation lens or a post-Council of Trent lens).

I have a slight problem with Brian McLaren’s graph from p. 34 of A New Kind of Christianity. His graph is shown above in the picture; my revised version is shown below.

McLaren places Eden on the level of Heaven which basically equals perfection. That might bother some but it doesn’t bother me. The only difference between my graph and his is the direction of the “Hell/Damnation” arrow. While nitpicky, I have a fundamental disagreement with McLaren on this one.

From a theological perspective, what bothers me is the downward direction of the arrow. Perhaps he drew it that way because we always think of heaven as existing above and hell existing below. I redrew it to make it a continuous straight line not only because I have semi-OCD tendencies but also because the destination as a result of condemnation is hell/damnation. It’s not a downward trajectory from condemnation but rather, a continuous path that is not separate from it. According to the Bible, this is the spiritual path that all souls are on as a result of the fall (Romans 5:17-19).

I’d also like to add that I’m interested in reading McLaren’s response to the pluralism question: “How should followers of Jesus relate to people of other religions?” On page 21, he briefly summarizes what he’ll try to address:

So we ask: Is Jesus the only way? The only way to what? How can a belief in the uniqueness and universality of Christ be held without implying the religious supremacy and exclusivity of the Christian religion?

I think it’s an interesting question to posit and answer, oops, I mean “respond to.” (There are no answers according to McLaren, only responses in an effort to stimulate and continue conversation. For a great Biblical counseling perspective on this conversation, check out Bob Kellermen’s series in which he provides responses to McLaren’s questions.)

So here are my initial responses before reading the chapter in which McLaren expounds on the pluralism question:

I’m excited about reading through A New Kind of Christianity. I have an open mind about this and am totally willing to transform my Christian faith and live it in a new way with only one caveat: it must remain true to the Bible. If McLaren argues something that goes against what the Bible says, I’ll point it out. We know very little about Jesus apart from the Bible. And we would know nothing about Jesus’ teachings without the Bible. So holding McLaren and his questions and responses to a Biblical standard is neither unreasonable nor unfair since he is talking about the the Christian faith.

I hope you’ll join me in my journey through this book. If you don’t know who Brian McLaren is or what a little bit of background on what part of the Christian faith he comes from, please check out my series on the emergent movement.

I’m reading through Brian McLaren’s A New Kind of Christianity and will post my thoughts on my blog as they strike me. You can find the first one here: http://bit.ly/8YYns6. I am working on a second.

For blog posts from a Biblical counseling perspective, please follow Bob Kellermen’s series.

A quote I found interesting:

When you talk to the people who walk down the aisle at a Billy Graham crusade to make a “first-time Christian commitment,” who say something called the “sinner’s prayer” in response to an evangelistic invitation, or who join a new church, you discover that over 90 percent of them are already lifelong churchgoers. That means that over 90 percent of the so-called new converts come from the 40 percent of the population who are already “in the choir,” and less than 10 percent come from the “unchurched majority.” So we have a lot of Baptists becoming Pentecostals, and Catholics becoming Episcopalians, and so on, but surprisingly few “unchurched people” getting connected with the church. (p. 4)

McLaren’s point is interesting in light of this piece from the Huffington Post, “Listen Up, Evangelicals: What Non-Christians Want You To Hear”: http://is.gd/aaCCI. An observation from this piece that struck me:

“I have no problem whatsoever with God or Jesus – only Christians.”

Sad. I have heard this from other Christians as well.

I’m not writing a book review on Hear No Evil because I wasn’t planning on it. But as I read through Matthew Paul Turner’s book, I wanted to offer a few thoughts. (Thanks to Jezamama for sending the book to me after winning her book giveaway contest!) I found some choice quotes that seemed especially insightful to me:

I’m not writing a book review on Hear No Evil because I wasn’t planning on it. But as I read through Matthew Paul Turner’s book, I wanted to offer a few thoughts. (Thanks to Jezamama for sending the book to me after winning her book giveaway contest!) I found some choice quotes that seemed especially insightful to me:

“The odd thing about Christians pursuing fame is that they do it while pretending not to be interested in fame. Their goal, most say, is not to bring fame and fortune to themselves. Their only interest is to make Jesus known. But in the process of making Jesus better known than he already is, a lot of Christian musicians find fame and fortune for themselves too.”

This thought gets to the heart of two main things about Christians:

Turner does an especially great job at illustrating this through his encounter with Jeff and Jack. (Btw, the section where he describes meeting Poppa Gladstone and going to his concert was HILARIOUS to me.)

Another quote that jumped out at me:

“I liked being Calvinist because it made me feel controversial and edgy to believe something different than what my parents believed. … I think that’s why people like Josiah and me sometimes turned into Calvinists. We could be passive-aggressive toward our parents and our past lives without being considered unchristian. Reformed doctrine offered a different way to think about God. And sometimes different, even when it really isn’t that different, is all we need to make us feel alive, creative, and in control of our own destiny.”

I’m part of a Christian message board in which the Calvinism vs. Arminianism debate is as worn out as a pair of sandals on a Middle Easterner. But a recent debate I engaged in questioned whether young people adopt Calvinism to buck responsibility. Turner sums the adoption of Calvinistic thought among young adults much better than I could have ever thought to put it.

Overall, I found Hear No Evil to be a humorous and an amazingly well-written book.

I didn’t grow up Independent Fundamental Baptist (IFB) but it is amazing how I was able to relate to many of Turner’s anecdotes despite my short stint in that realm in young adulthood. In a way, Hear No Evil is really Chicken Soup for the Recovering Independent Fundamental Baptist’s Music Soul. Turner’s book on his general IFB experience, Churched, is on my must-read list now. You can connect with Turner on his blog at http://jesusneedsnewpr.blogspot.com or through Twitter: http://www.twitter.com/jesusneedsnewpr.

—

Apologies for not providing page numbers for the quotes. I’m already shipping the book off to a friend who lost a contest to win the book. This book is too good to keep to myself.

February 28th marks the end of Black History Month for 2010—something I chose not to take part in this year. Not because I have any personal objections to commemorating Black American history or anything; I was simply preoccupied with other things like reading up and writing about the Emergent Church. I also read the hardcover version of Joseph C. Phillips’s book, He Talk Like A White Boy, and had hoped to provide a review sometime during February but upon receiving the paperback version, I discovered more essays were added so a book review on that has been put on hold for now.

For some time, I have been mulling on and off about the issue of Black pride. A counter in this discussion is often, “Why is it okay for people to have Black pride and if a White person has White pride, it’s White supremacy and racism?” While I can see that as a valid argument, I submit the idea that Black in America has evolved from a purely racial context to a mostly cultural context.

Many white people (or Caucasians) in America likely know their ethnic background based on their last name or some kind of genealogy. No one knocks Italian-Americans for having Italian pride or Irish-Americans for celebrating their heritage on good ol’ St. Patty’s Day. Americans who have an Italian or Irish background are, quite frankly, part of the White race but choose to emphasize their ethnicity rather than simply the color of their skin. Even those who are of white supremacy organizations are known as WASPs (White Anglo-Saxon Protestants). This WASP indication places them in the context of British, Germanic, and possibly even Danish ethnicity. I daresay most people don’t have a problem with Americans celebrating their Polish or Germanic heritage.

But when it comes to Black people, they are slammed for choosing to identify themselves as African-American: “Oh, you’re not really African-American. Look at Kwame over there. His parents are from Zimbabwe—he’s a real African-American.” So what are Black people in America?

Well, simply put, Black people in America are Black Americans. Should they choose to identify themselves as African-American, that is purely their prerogative even if the last ancestor that hailed from Africa was back in 1776. The fact of the matter is that most people who are considered Black in the United States are most likely of Sub-Saharan African descent.

But 1776 is a long way away from 2010. A Black American stepping onto African soil would feel strangely at home and strangely out of place at the same time. Joseph C. Phillips writes:

There is a romanticism associated with Africa that runs deep in the black community. … For me, the bloom fell off the African rose fairly early. Maybe it was when a soldier armed with an AK-47 boarded our bus on the way to the hotel. Or maybe it was when I realized Nigeria was so rife with corruption that cashing a traveler’s check was a major ordeal. The romance was certainly gone once we drove through the countryside and witnessed poverty like I have never seen before. … Alas, my visit to Africa proved less of a homecoming than an affirmation of my Americanness.

… Later in the trip, I had an opportunity to meet socially with several Nigerians. Among my fellow travelers there was a tendency to speak of American blacks as if we were Africans living abroad, everyday Africans did not share this view. They saw us as Americans, first and always. Even to the Nigerians I met who, by and large, were educated in the West we were as American as, well, George Bush.

… That’s not to say I did not feel the tug of Africa at all. I discovered that it is very difficult to be a black American and experience Africa purely as an American. Everywhere I looked, there were bits and pieces of myself.

Black Americans, like Italian-Americans, Irish-Americans, or Polish-Americans, are very much African but moreso very much American.

The estimated date for final importation of slaves from Africa is in the mid-1800s. That leaves a century and a half in which generational Black Americans are most likely to have had ancestors directly from Africa. Within two centuries, however, Black Americans have evolved from African culture and developed their own kind of culture relative to the United States alone. As a result, being Black in America is not simply a matter of race, it is also a matter of culture. Race and culture are now inevitably intertwined.

So when I think of Black pride, I don’t necessarily think of Black Americans taking pride in the color of their skin but rather who they are as a culture that happens to be connected to the color of their skin. I do like the way the writer of the wikipedia entry on African American culture put it:

For many years African American culture developed separately from mainstream American culture because of the persistence of racial discrimination in America, as well as African American slave descendants’ desire to maintain their own traditions. Today, African American culture has become a significant part of American culture and yet, at the same time, remains a distinct cultural body.

There is a style of worship, a style of music, a form of art, and a form of dance that is intrinsic to Black American culture. While some of it may be derived from Africa, it has evolved over the centuries to become uniquely Black American (or African-American, if you will).

There is a style of worship, a style of music, a form of art, and a form of dance that is intrinsic to Black American culture. While some of it may be derived from Africa, it has evolved over the centuries to become uniquely Black American (or African-American, if you will).

But then I wonder whether if it’s sinful to have Black pride within a cultural context and I don’t believe so. Just like the ethnic pride of being Spanish, Germanic, or Swedish, I don’t believe pride in immutable, nonsinful qualities is wrong—it’s the way God made us! Where it does start to go wrong is when these groups use their ethnic position as a form of superiority, especially in order to oppress one group over another. Black supremacy is just as wrong as white supremacy, no matter what the context.

So when I think of Black History Month, and heading into March Women’s History (or Herstory, whatever you want to call it) Month, I don’t see such remembrances as an issue of superiority of one group over another (black vs. white or male vs. female). Rather, I see them as a way of celebrating and reflecting on the accomplishments of formerly oppressed groups that overcame significant obstacles to become thriving members of American society.

When it comes to looking at other female Christians, I’ve always felt like an outsider. Through the lens of my “doo doo” eyes, these females tend to be white, wholesome, and happy. Now that I run with the 30 and older crowd, they also have babies or toddlers. I tell myself I’d die if I were a mommy blogger. I don’t mind being a blogger who happens to be a mom but adding “mommy blogger” to my job description would just about kill me.

Or maybe not. Because I have no problem being a sellout because I am that desperate for acceptance. On a forum I frequent, someone posted a link to a job description as a reporter for a popular politically conservative website. I’m not particularly conservative politically but I’m not liberal enough for the Huffington Post either. But I’d spout conservative principles if I had to just for the opportunity to write for a living. Unfortunately, on the liberal side, I’d only go so far since the abortion issue is a big problem for me. If I could blog as a pro-life liberal, I’d be okay on that end.

My counselor in Kentucky used to say to me and my husband, “People desire two things in life: to be right and to be accepted.” I so would prefer to be accepted than to be right. If all the conservatives hated my political views but thought I was an otherwise cool chick, I’d be ecstatic. I don’t care if my friends think I’m a total idiot as long as they love me anyway.

The only time I’ve ever felt accepted by a group in my entire life was when I joined a sorority at the first (secular) college I attended. In a sense, I feel like I earned the ability to be accepted. I left the college shortly after so my feeling of acceptance by my sorority sisters was short-lived.

The feeling of acceptance decreased ever since. I attended a fundie Christian college for a few years where I stood out like a sore thumb in various ways: my shirts were too tight or too see-through (even though I didn’t think they were all that bad); I didn’t have a plethora of skirts or dresses I could rotate through; I didn’t look or think as wholesome as those other homeschooled Christian girls; I wasn’t as naive (or maybe I was). I moved joyfully to the melody of hymns during church services while the few friends I had desperately crowded around me to make sure I didn’t get in trouble for moving in time to the rhythm of the music. (I called myself “Bapticostal” during that time.) What was wrong with dancing to music? Didn’t David dance joyfully while worshiping the Lord? Gosh, I was such a freak.

I still think of myself as a freak. Continue reading “Midnight ramblings”